Recent developments in Finnish language education policy.

A survey with particular reference to German

Chris Hall, Joensuu

As a country whose main national language is hardly spoken outside its borders, Finland has always recognised the importance of foreign language learning. The official language education policy which has been in place in Finland for the last 30 years emphasises the importance of offering a wide range of foreign languages at schools so that the whole of the educated population has a command of Finnish, Swedish and English, and a sizable proportion also has a knowledge of German, Russian and French.

This language education policy has not changed. However, in recent years there has been a dramatic transformation in the languages taught at Finnish schools in that English gained ground at the expense of German and other foreign languages, the second national language Swedish is no longer an obligatory part of the matriculation examination, and that there has been an overall reduction in the number of foreign languages learned.

This trend also has repercussions for universities and other tertiary institutions. A government-sponsored report on the situation was published in April 2007, which lists a number of options for language education policy in Finland. This paper will analyse the current situation and trends in Finnish language education with special reference to German. A comparison is also made with developments in Sweden and the UK.

1. Introduction

Finland is officially a bilingual country with a majority language, Finnish, and a minority language, Swedish. These two languages are completely unrelated, as Finnish is a Fenno-Ugric language (related to Estonian and Hungarian) and Swedish is a North Germanic language. From the founding of the Republic in 1917 Finnish and Swedish have had official status based on the Language Act (kielilaki) of 1922 (revised 2004), which is widely considered to be an exemplary document of its kind.

Apart from the two national languages, foreign languages (FLs) are very important in Finland, as Finns need a knowledge of other languages in their dealings with the outside world. The purpose of this article is to examine the language policy which has applied to the two national languages and to FL teaching in Finland with special reference to the teaching of German.

2. Background: Languages in Finland

In the Middle Ages, especially since the 17th century, Finland was part of the kingdom of Sweden, and Swedish was the language of government, the upper classes and of a section of the population.

Map 1: Finland and neighbouring countries

(Map by Timo Pakarinen, Department of Geography, University of Joensuu)

It was not until 1863 that Finnish gained equal status with Swedish, and it was not until 1902 that Swedish dominance was finally broken with the ratification of the communal language principles (cf. Piri 2001: 102f.).

Since independence from Russia in 1917, the goals of Finnish language policy have been to guarantee the rights of the Swedish-speaking minority to use their own language and to guarantee the rights of Finnish-speakers to use their language in Swedish-speaking areas.

Linguistic equality has been important in Finland for two reasons:

· For reasons of national unity it is important for the members of the two linguistic communities to understand each other.

· Finland is a member of the Nordic Community (together with Sweden, Norway, Denmark and Iceland) and it has been a high priority to maintain links to the other Nordic countries (which speak Swedish or a closely related language). A knowledge of Swedish has been considered essential for this.

The number of Swedish speakers in the early 1600s was 17,5%, at independence in 1917 over 11%. According to the latest figures available (from 2006) the present proportions are: Finnish speakers 91.5%, Swedish speakers 5.5% (Statistics Finland 2007). The Swedish-speakers are concentrated in areas along the west and south coasts and in the Åland Islands.

Apart from Finnish and Swedish there are three other officially recognised languages in Finland. Sámi is spoken by an indigenous group of fewer than 2000 speakers who live in the extreme north of the country. Romany and sign language are also officially recognised.[1]

3. Foreign language education in Finland

The aims of language education policy in Finland have been

a) to ensure an adequate knowledge of both national languages (necessary to meet the legal and practical requirements of a bilingual country), and

b) to ensure a knowledge of a wide spread of FLs (necessary for international co-operation).

The learning of the second national language, Swedish, has always been obligatory for pupils at secondary school, and FLs have also played a major role in Finnish schools since before Finnish independence in 1917. This can be seen from the following table, which lists the proportion of time (by number of lessons) devoted to various groups of subjects for 4 schools towards the end of the period of Russian rule: [2]

Table 1: Language subjects in Finnish schools towards the end of the period of Russian rule

Subject groups |

Lyseo |

Reaalilyseo 1883 |

Klass. Lyseo 1914 |

Tyttölyseo 1915 |

1. Finnish 2. Theoretical subjects 3. Mathematical subjects 4. Languages 5. Practical subjects |

4.9 23.2 20.1 50.1 1,7 |

5.6 22.5 21.2 35.3 15.4 |

8.4 22.7 14.3 42.2 12.4 |

9.7 23.3 16.5 28.1 22.4 |

The most important languages were Swedish, Russian and German, followed, at some distance, by French and English.

In the following sections we will look at Swedish and the other FLs separately because of the special role Swedish has as the second national language.

3.1 Swedish

The status of Swedish in Finland is determined by the Language Act and by Finland ’s membership of the Nordic Community. The Declaration on Nordic Language Policy (Nordic Council of Ministers 2006) is not binding on the member states, but in practice their language policies conform to it. The Declaration lists five aims, including (2) that all citizens of the Nordic countries should be able to communicate with one another primarily in one of the Scandinavian languages (Declaration, p. 2).

The Helsinki Treaty between the Nordic countries came into force in 1962. Art. 8 states that: “Educational provision in the schools of each of the Nordic countries shall include an appropriate measure of instruction in the languages, cultures and general social conditions of the other Nordic countries.”

From independence in 1917, the second national language Swedish (or Finnish for Swedish-speakers) was obligatory in the old grammar school (oppikoulu), and it was made obligatory for all pupils from year 7 when the comprehensive school (peruskoulu) was introduced in 1968. The obligatory nature of Swedish has been a matter of some debate in Finland, but so far, it has remained an obligatory subject for all pupils at secondary schools. However, since 2005 it has no longer been an obligatory part of the matriculation exam. Most pupils continue to take it, however, because a knowledge of Swedish is required by law for all higher positions in the civil service and in practice for most higher positions in commerce, the law and industry, which is a strong incentive for pupils to gain qualifications in Swedish at school.

On the other hand, it is true that Swedish is no longer as important in Nordic co-operation as it used to be. Younger Finns often find it easier to communicate with people from other Nordic countries in English than in a Scandinavian language; English is nowadays used in many Nordic multinational companies, not least because the Finns feel at a disadvantage using Swedish, and it is even creeping in in contacts between Finland and Sweden at the highest political level (see Blåfield 2006).

On the whole, however, there is very strong support in Finland for the country’s bilingual status. According to Allardt (1997), 70% of Finland’s Finnish-speaking population feel that Swedish is an essential part of Finnish society, and 73% believe it would be a pity if the Swedish language and culture were to die out completely in Finland.

3.2 Other foreign languages

In the early years of independence the position of German was very strong in Finland , not only in the schools, but also as a language of science[3], and educated people spoke German and were familiar with German culture.

After WWII, efforts were made to strengthen the position of English and Russian “for general political reasons” (Piri 2001: 113). By the early 1960s English had overtaken German as the first FL at the grammar school (oppikoulu). The figures for 1962 were: English as first FL 56.9%, German 42.6%. The decline was even stronger in the following decade: between 1962 and 1974 the percentage learning German at grammar school went down from 57% to 8%. French, Latin and Russian remained at about 1% during this period (Piri 2001: 114).

The groundwork for the current Finnish language education policy was laid in the 1970s with a detailed survey of Finland’s foreign language needs by the Language Programme Committee (Kieliohjelmakomitean mietintö 1978). Since then the main aim of Finnish language education has been the provision of as wide a range of FLs as possible at all levels of the education system. In their 1978 report, the Language Programme Committee determined 4 levels of command of a language (adequate, satisfactory, good, very good) and set the following ambitious targets:

· For Finnish, Swedish and English: 100% of the adult population should reach levels 1‑4 with 50% at level 2 (good)

· For German and Russian: 30% should reach levels 1-4

· For French: 15-20% should reach levels 1-4.

Adult population means 20-63 year-olds, and the goals were to be attained in a period of 30-40 years, 2010-2020 (Piri 2001: 133f.).

With this policy, Finland was at the forefront of language education policy developments in Europe, fulfilling the objective of the European Commission’s White Paper Learning and Teaching before it was formulated in 1995: that every EU citizen should have a knowledge of at least two EU languages in addition to her/his native language (European Commission 1995: 47–49).

The system which has evolved at schools over the last three decades consists of two obligatory and several optional FLs (Table 2):

Table 2: Foreign languages at Finnish schools

Status |

Starting point |

|

compulsory |

Year 3 |

|

A2 |

optional |

Year 5 |

B1 |

compulsory |

Year 7 |

B2 |

optional |

Year 8 |

B3 |

optional |

Year 10 (Year 1

of upper |

Pupils usually begin studying their first FL in year 3 (first compulsory FL). Pupils in years 1-6 may also begin an optional language. A second FL is added in the lower secondary school (years 7-9). If Swedish (or for the Swedish-speaking minority Finnish) is not the A1 language, it must be taken as the B1 language. Pupils at lower secondary level can also take another optional language.

English is nowadays by far the most popular FL. In 1997, 93% of pupils in years 3-6 and 99% of those in the lower secondary school chose it as either a compulsory or an optional language. One fifth of the pupils in the lower secondary school took German and 8 per cent French. (Table 3):

4. Recent developments in Finland

In recent years the development has taken a sharp turn in exactly the opposite direction to the one which the Language Programme Committee had hoped to encourage in that:

· FLs are being learned less rather than more,

· the range of FLs learned at schools is narrowing rather than broadening, and

· the time spent learning FLs at schools is lessening rather than increasing.

The continuing growth of English is accompanied by a decline in the study of other languages. English is now the A1 language for approximately 90% of schoolchildren and the second national language (for the majority Swedish) is taken by all pupils as the B1 language if they have not taken it as A1. Additional optional FLs are becoming less popular.

This development runs counter to the aim of providing a wide range of FLs. This is not because the aims of the Language Programme Committee had become less relevant in the intervening decades. On the contrary, the relevance of these aims was underlined by a number of events in the 1980s and 90s, notably German unification and the strengthening of Germany’s position in the EU (increasing the importance of German), and Finland’s membership of the EU in 1995 (increasing the need for major European languages such as German, French, Spanish and Italian). Even the weakening of Russia after the break-up of the Soviet Union in 1991 did not do away with the need for Russian in Finland, since Russia remains Finland’s largest and most powerful neighbour and a very important trading partner.

Numerous surveys of the business community have showed that languages are considered very important. For instance the Prolang project funded by the Finnish National Education Board (FNBE, Opetushallitus) in the late 1990s showed that English is needed by 100% of the companies surveyed as one of the three most important languages, Swedish by 86%, German by 68%, Russian by 17%, French by 13% and Spanish by 4%. Other languages, Italian, Chinese, Estonian and Japanese, were needed to a lesser degree (Huhta 1999: 62f.).

Concern about the narrowing of the range of FLs taught at schools led to a major government-funded project to encourage the learning of a wider variety of languages at Finnish schools, which will be discussed in the next section.

4.1 The KIMMOKE project

The KIMMOKE project (Kieltenopetuksen monipuolistamis- ja kehittämishanke, ‘Project for the diversification and development of language teaching’) was undertaken in the period 1996-2001 (and partly until 2004). A total of 275 schools and other educational institutions in 39 municipalities took part in the project whose principal aims were to broaden the range of FLs taught at Finnish educational institutions and to develop FL teaching, including assessment, in the participating institutions. Further aims were the development of Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) in which other subjects, e.g. geography, are taught through the medium of a FL, improving international links, and the development of oral skills. Funding was provided by the Ministry of Education.

The concrete goals of the project for schools were:

· A threefold increase in the numbers studying Russian and a 10–20% increase in the numbers studying German, French and Spanish, without affecting the numbers studying English and Swedish

· That optional A2-languages should be available everywhere

· A rate of 50% of pupils in years 7–9 taking an optional FL without marked differences between the sexes

· A rate of 90% of pupils in the upper secondary school taking an optional FL without marked differences between the sexes.

Concrete goals were also set for language skills in vocational education.

None of these goals were achieved, partly because they were overambitious and partly because insufficient funding was provided, but there were some local successes and limited improvements in certain areas. In particular, German profited in some areas from the KIMMOKE project.

The following tables[4] show the development of FLs at comprehensive schools from the 1990s to 2005, the last year for which figures are available.

Table 3: A1 languages at comprehensive school in percentages

Language |

1996 |

2003 |

2004 |

2005 |

English |

86.6 |

90.5 |

90.7 |

89.5 |

Swedish |

2.4 |

1.3 |

1.2 |

1.1 |

Finnish |

4.6 |

5.3 |

5.5 |

5.5 |

German |

4.0 |

1.7 |

1.6 |

1.4 |

French |

1.7 |

1.0 |

0.9 |

0.8 |

Russian |

0.3 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

Those taking Finnish as a FL are, of course, mainly the Swedish-speakers. The trend for German at comprehensive school, as for Swedish, French and Russian, is clearly downward over this ten-year period. This is attributable partly to the general trend towards English and partly to the fact that in spite of the aspirations of KIMMOKE, in 90% of Finnish municipalities the only A1-language available to pupils is English (Sajavaara 2006).

A2 languages are available in less than 50% of municipalities (Sajavaara 2006), compared with the goal of 100% in KIMMOKE, and numbers have gone down from year to year:

Table 4: A2 languages at comprehensive school in percentages

Language |

1998 |

2003 |

2004 |

2005 |

English |

10.2 |

8.3 |

8.7 |

8.3 |

Swedish |

6.6 |

8.5 |

8.1 |

7.7 |

Finnish |

0.5 |

0.3 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

German |

16.2 |

11.0 |

9.6 |

8.6 |

French |

3.1 |

3.1 |

2.8 |

2.9 |

Russian |

0.5 |

0.3 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

English has gone down as an A2-language because more pupils are taking it as their A1-language. The same is true for Finnish. The falls in the numbers for other languages mean that optional A2-languages are becoming less popular.

The situation is very similar with B2 languages:

Table 5: B2 languages at comprehensive school in percentages

Language |

1994 |

2003 |

2004 |

2005 |

English |

0.7 |

0.2 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

Swedish |

0.2 |

0.1 |

0.3 |

0.2 |

Finnish |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

German |

27.3 |

8.7 |

7.9 |

6.6 |

French |

9.4 |

6.9 |

6.6 |

5.4 |

Russian |

0.9 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

0.6 |

All B2 languages |

39.4 |

17.7 |

16.7 |

14.1 |

The figures for B2-English, Swedish and Finnish are very low because the overwhelming majority of pupils take these languages as obligatory languages. The fall in the figures for other FLs is dramatic, especially the 75% fall in numbers for German.

Only in the upper secondary school (lukio), the final three years of secondary education in Finland, do the figures look healthier. In 2005, over 60% of those finishing the upper secondary school and doing their matriculation exam studied at least three FLs, which are of course a combination of A- and B-languages (compared with the goal of 90% set in KIMMOKE).

Table 6: A-languages in upper secondary school in percentages

Language |

2002 |

2003 |

2004 |

2005 |

English |

99.2 |

99.0 |

99.0 |

99.4 |

Swedish |

4.7 |

5.8 |

6.9 |

7.0 |

Finnish |

5.0 |

5.5 |

6.1 |

5.5 |

German |

4.6 |

7.6 |

9.3 |

10.3 |

French |

1.4 |

1.9 |

2.1 |

2.3 |

Russian |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.4 |

0.7 |

Table 7: B-languages in upper secondary school in percentages

Language |

2003 |

2004 |

2005 |

English |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

German |

22.9 |

21.4 |

17.7 |

French |

12.0 |

11.6 |

10.0 |

Russian |

2.2 |

1.7 |

1.7 |

Spanish |

2.8 |

3.2 |

3.6 |

Italian |

0.7 |

0.8 |

1.0 |

In the upper secondary school, the figures for German in particular, but also French and Russian as A-languages rose during this period as a result of the KIMMOKE project, accompanied by a smaller fall in the numbers of those studying these subjects as B-languages. However, since 2006 numbers for A-languages have been falling again, as the following table indicates for German:

Table 8: German as A1 and A2 language in Finnish matriculation exam

German A1/A2 |

Total |

Girls (%) |

Boys (%) |

1997 |

535 |

66,2 |

33,8 |

1998 |

579 |

66,5 |

33,5 |

1999 |

634 |

72,1 |

27,9 |

2000 |

696 |

69,3 |

30,7 |

2001 |

910 |

66,2 |

33,8 |

2002 |

1359 |

66,2 |

33,8 |

2003 |

1858 |

71,0 |

29,0 |

2004 |

2068 |

73,1 |

26,9 |

2005 |

2098 |

69,9 |

30,1 |

2006 |

1761 |

72,5 |

27,5 |

2007 |

1632* |

|

|

*Unofficial figure

(Source: Ylioppilastutkinto 2006. Tilastoja ylioppilastutkinnosta.)

It is noticeable that there are three to four times as many girls taking German as an A-language as there are boys, which means that the number of boys taking German as an A-language is very small indeed.

The figures show that the KIMMOKE project helped for a short while, especially for German, but that when the funding ended the numbers learning German and other FLs went down again quickly. KIMMOKE also opened up opportunities for local initiatives, for instance in the small southern Finnish municipality of Halikko, where active teachers, support from the Finnish National Board of Education and an international project (NEOS – Network of Europe Oriented Schools) led to a very high take up of German courses.

4.2 Reasons for the recent trend in Finland

The Ministry of Education and the FNBE are concerned by the recent trends, as they would like to see a wide range of FLs taught at Finnish schools. There are probably two main reasons for the current trend[5]:

· The local authorities decide on the school curriculum in their areas. In order to save money, many of them cut back on non-obligatory subjects like optional FLs, and

· Pupils and their parents are choosing English as their first FL and are not choosing optional FLs to the same extent as they used to.

But there are also many other reasons:

· Until 1998 municipalities with over 30,000 inhabitants were obliged to offer English, German, French, Russian and Swedish as A-languages. In 1998 this obligation was removed.

· Swedish has been affected by the reform of the matriculation exam in 2005, in which the subject ceased to be obligatory.

· The reform of the “reaali” subjects[6] in 2006 made it easier to take at least two (max. six), reducing the popularity of FLs, which are seen to be “difficult subjects” in comparison with e.g. geography, history or the newly introduced health studies.

· The new course-based structure of the upper secondary school has had a negative effect on FLs because it makes it easy for pupils to give up “difficult” languages for easier subjects after a number of courses.

· The distribution of lessons does not favour optional FLs. They tend to get the slots which are left over from obligatory subjects.

· There are more applicants to study English at universities but less interest in other FLs, e.g. because there will be far fewer teaching posts in these subjects at schools in future.

· University entrance: most universities do not give extra points for a second A-language, which means that applicants get the same number of points for a B-language as they would for a second A-language.

· An attitude of “English is enough” seems to be spreading, possibly because of the dominance of English in the media, because Finnish politicians and business leaders can frequently be heard speaking publicly in English but rarely in other FLs, etc.

Only two of these factors, the removal of the obligation of larger municipalities to offer a choice of five A-languages and the change in the status of Swedish in the matriculation exam in 2005, have been deliberate changes to the detriment of language subjects. All the others have had a negative effect on FLs as a by-product, unintentionally.

4.3 The KIEPO project

The KIEPO project (Kielikoulutuspoliittinen

projekti – Project on Finnish

Language Education Policies) was a national project funded by the Ministry

of Education and coordinated by the Centre for Applied Language Studies at the

The KIEPO working party made several short-term recommendations for strengthening the present language programme and long-term recommendations for developing a new one.

1. The recommendations for strengthening the present language programme recognise that it takes time for changes to work their way through the system. They include the following:

· Reduction in the minimum size of groups. Group sizes have been raised in recent years, which means that it is more difficult to offer teaching in the lesser taught languages.

· Joint teaching positions in lesser-taught languages shared by several schools.

· Networks of schools to form sufficiently large groups, especially in German, French and Russian.

· Increased utilisation of internet-based and distance learning techniques, and co-operation between schools.

· Better use of language learning opportunities outside the schools (e.g. media, study trips, international projects).

· Systematic support for immersion courses and CLIL.

· The creation of schools specialising in languages and cultures.

Some of these recommendations require considerable resources, e.g. smaller groups or specialist language schools, but others may lead to modest savings.

2. The recommendations for the long-term development of the language programme are presented in the form of five alternatives (A–E) which involve either two or three obligatory FLs plus optional ones. The exact combinations of languages and the starting points of their study differ in the various options (cf. Luukka & Pöyhönen 2007: 17–26).

Which of the options, if any, will be chosen is up to the politicians. The KIEPO proposals have generated a certain amount of discussion in educational circles, but the general discussion in the media has been disappointing. In spite of widely professed concerns and irrefutable evidence of the narrowing range of FLs taught at Finnish schools, few people seem to regard it as a priority to take measures to counteract this trend.

4.4 Current position of German in Finland

At present, German is still one of the strongest FLs in the Finnish school system. On the one hand its position is under threat in that:

· English is seen by many as an international language which makes the learning of other languages unnecessary,

· Over the last three or four decades German culture has lost out to the attractiveness of Anglo-Saxon culture, especially in the eyes of young people, and more recently Spanish is proving to be an attractive alternative to German,

· German is perceived by some as a difficult language,

· The need for the municipalities to save money means that minimum group sizes have increased, frequently to 14–18, and it is becoming more and more difficult to provide courses in German and other FLs even when the demand is there.

· As German is learned less and less at schools, the level of German teaching at universities and in adult education is going down (more beginners’ courses and less advanced courses),

On the other hand German has certain strengths compared to other FLs:

· Although it no longer has the leading position it did in the first half of the 20th century, after English it is still the most frequently learned FL,

· it is a natural choice for a second FL as there is a long tradition of learning German in Finland,

· the language is closely associated with certain areas, e.g. technology,

· the cultural, economic and personal links between Germany and Finland mean that German is regarded as a useful language in Finland.

While German is undoubtedly on the defensive in Finland at present, it is by no means inevitable that its downward slide will continue, especially as there is agreement among leading politicians and business people that Finland needs German and Russian speakers. Action will be required, however, for instance the implementation of the KIEPO recommendations and increased funding for FLs at schools. The experience with the KIMMOKE project shows that even a moderate amount of additional funding has a positive effect and that the withdrawal of funding has a negative effect.

5. Trends in two other countries

In this section I present a brief survey of the situation in Sweden and the UK to see how the development observed in Finland fits in with those in other countries.

5.1 Sweden

The switch from German to English as the first FL at school happened earlier in Sweden than in Finland , in 1946, shortly after the end of WWII. Nowadays English is an obligatory subject from the first year through to the matriculation exam. A distinction is made between English, which is obligatory (former A-language) and additional “Foreign Languages” (former B- and C-languages). The first of these additional FLs (former B-language) is started in year 6 (in 1999 by 80% of pupils) and in years 7–9 it was studied by 98% of pupils in 1999. The most popular languages are German, French and Spanish, but tuition in the mother tongue, Swedish as a second language, English or sign language may be offered instead of the B-language if the pupil or their parents so wish. It is possible to take a second FL (former C-language) in year 8 of the comprehensive school, but this is not common (in 1998-99 only 4.6%, Malmberg 2000: 10). A second FL is taken in greater numbers in the upper secondary school.[7]

Recent issues in FL education policy in Sweden have been

· The reduction in the number of lessons in languages, which has led to a lowering of the levels achieved by pupils (cf. Jämförelse mellan gamla och nya kurser för språk).

· The fact that the study of languages apart from English is not being continued in the upper secondary school. Between 1997 and 2001 the number studying a B-language in the upper secondary school fell from 32% to 16% and the number studying a C-language fell from 28% to 14%. This is in part due to the introduction of popular alternative courses including “Manikyr” (manicure) and “Vinkunskap” (wine studies). The Swedish government which took office in 2006 is taking measures to improve the attractiveness of B- and C-languages in the upper secondary school by giving additional points for university entrance (Leijonborg 2007).

It is clear that there is considerably less teaching of FLs at schools in Sweden than in Finland . There is also no Nordic dimension to FL teaching in Sweden , as the population already speaks the largest Scandinavian language either as their mother tongue or as a second language.

5.2 UK

In the UK there have been a number of surveys of the position of FLs in education, the most recent being the report of the Nuffield Languages Inquiry, Languages: the next generation (McDonald & Boyd 2000) and the Languages Review (Dearing & King 2007).

Dearing & King note that in September 2004 learning a language ceased to be a mandatory part of the curriculum for pupils in the last two years of compulsory education and became instead an entitlement for all pupils who chose to continue after taking an obligatory FL in the previous three years.

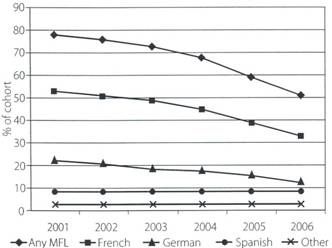

While the take up of FLs in British primary schools (i.e. years 1–6) has been good, rising to 70% in 2007, the situation in secondary schools is marked by decline, see fig. 1:[8]

Fig. 1: Percent of cohort taking a FL at GCSE

The Languages Review expresses concern about the current situation in the UK and makes a number of recommendations including:

· Investment in teachers in primary and secondary schools

· That FLs should be compulsory for the age groups 7 to 14

· An increase in the number of schools with a specialism in FLs to 400 (from 300 at present)

· More “engaging” courses and a reform of the GCSE exam, which is widely believed to be “lacking in cognitive challenge” for higher achievers

· Encouragement for a wider range of FLs, including Asian languages

· Support for CLIL and immersion courses

· To make the case for FLs to all sections of the population

· To encourage employers to promote the value of FL skills for business

· If encouragement does not work within a reasonable period they propose a return to a mandatory curriculum, in other words to make FLs compulsory subjects again for the age groups 14+.

The goal of these recommendations is to lift the numbers choosing to take FLs at 14+ to 50–90%.[9]

Dearing & King estimate the cost of implementing their recommendations at over £50 million a year (2007: 2). Some of the recommendations were immediately backed by the Minister of Education, and a budget of £50 million is available for the current year.

An interesting point is that Dearing & King found evidence of a link between performance in FLs and social class in the UK:

· The proportion of pupils entitled to free school meals (i.e. pupils from the poorest homes) who gained a qualification in FLs at age 14+ is only half that of pupils from better off homes

· The proportion of pupils taking FLs who obtained one of the top grades (A*–C) in at least five subjects at GCSE is about twice that of the less successful pupils (Dearing & King 2007:4).

No such link between performance in FLs at school and social class has come to light in Finland or Sweden. The situation in both these countries is, of course, radically different from that in the UK , where according to Hawkins (1981: 97) teaching a language is like “gardening in a gale” – you plant the seeds and then the seedlings are blown away by the gale of English from one lesson to the next. There is a much greater interest in and contact with FLs among the population at large in Finland and Sweden (e.g. via television and the internet) than in the UK . The recommendations of the Languages Review, if implemented, would move the UK towards the current Swedish position, but it is highly unlikely that FLs could be taught with the same intensity in the UK as they are in Finland .

6. Discussion

Politicians and educational administrators in Finland say they are concerned by the recent narrowing in the range of FLs offered at the country’s schools. The trends examined here are a good example of how drift can occur without any concrete decisions by policy makers if pressures exist in society.

Politicians carry the greatest responsibility for the development because they are in a unique position to influence events by passing laws and providing funding. However, recent developments in the FLs learned at Finnish schools clearly show the limits of politicians’ influence. If they choose not to legislate or provide funds they are just as powerless as the rest of us, and exhortations are simply not effective if there are pressures influencing developments in other directions.

One of the foremost authorities on language education in Finland, Sauli Takala (1993: 68), writes that “the best and only trustworthy guarantee that language learning opportunities will be utilised is to make the language study compulsory” in education, and adds that if this is thought unacceptable, the extent of FL study can still be influenced by giving rewards for each FL studied (extra credit points for university entrance, etc.). He writes that Finnish university departments thoughtlessly guide students in the “English-only direction” by failing to give alternatives for set books in different languages. Finally he suggests universities could send a message to school pupils by charging for low-level language courses they have to arrange for students who have chosen not to take languages at school. This last proposal is not permissible under current Finnish law, however.

We have seen that the main elements mentioned by Takala, compulsory language courses at schools and rewards for each FL studied, have been employed to varying degrees in Finland, Sweden and the UK. Takala does not suggest making it easier for pupils to take FLs by providing adequate funding to enable a variety of courses to be offered and to reduce minimum group sizes. This is not a simple matter in times of financial constraint and competing demands on the public purse, but if change is to be achieved some funds will have to be made available in Finland, as is proposed in the UK, as it is more expensive to offer a wide range of FL courses than just one or two.

In all three countries FLs have suffered, in different ways, from the success of English. Reversing recent trends will require considerable effort and a combination of measures, but suggestions for action are to be found in the KIEPO report, the Languages Review and the measures taken by the new Swedish government.

In this article I have concentrated on the effects of Finnish language education policy in the schools, because there are no comparable statistics for languages in vocational education, adult education or in the workplace. In vocational education it seems clear that it is rare for students to study languages other than English and Swedish. In adult education and the workplace the situation is probably different, but little is known about the level or extent of the language teaching which takes place there.

Bibliography

Allardt, Erik (1997) Vårt land, vårt språk. Tvåspråkigheten, finnarnas attityder samt svenskans och finlandsvenskarnas framtid i Finland [Our country, our language. Bilingualism, the attitudes of Finns and the status and future of Swedish in Finland]. Finlandssvensk rapport nr 35. Helsinki: Helsinki University Press.

Blåfield, Antti (2006) Pienen pieni uutinen [A tiny piece of news]. In: Helsingin Sanomat 19.10.2006.

Dearing, Ron; King, Lid (2007) Languages Review, London: Department for Education and Skills. Online: http://www.teachernet.gov.uk/_doc/11124/LanguageReview.pdf (accessed 3.10.07)

Skolverket [National Agency for Education] Descriptive data on childcare, schools and adult education in Sweden 2000, 2003, 2006. Stockholm: Skolverket. Online: www.skolverket.se/sb/d/356/a/1326;jsessionid=45CAC0ED313AC6FE7FE69649669BB9B5 (accessed 5.11.07)

European Commission (1995): Teaching and Learning – Towards the learning society. White paper on education and training. Brussels. Online: http://ec.europa.eu/education/doc/official/keydoc/lb-en.pdf.

Hawkins, Eric (1981) Modern Languages in the Curriculum, Cambridge Educational.

Huhta, Marjatta (1999) Language/communication skills in industry and business. Report for Prolang/Finland. Helsinki: National Board of Education. Online: http://www.edu.fi/julkaisut/skills42.pdf.

Jämförelse mellan gamla och nya kurser för språk [Comparison between old and new language courses] (no date) Myndigheten för skolutveckling [The Swedish National Agency for School Improvement]. Online: www.skolutveckling.se/innehall/kunskap_bedomning/sprak_las_skriv/sprak/kursplaner/jamforelse_mellan_gamla_och_gallande_kurser_for_sprak/ (accessed 5.11.07).

Jungner, Anna (2007) Swedish in Finland. Online http://virtual.finland.fi/netcomm/news/showarticle.asp?intNWSAID=26218 (accessed 25.10.2007).

Kieliohjelmakomitean mietintö [Report of the Language Programme Committee] (1978) Komiteanmietintö 1978:60. Helsinki: Ministry of Education.

Kieltenopetuksen kehittäminen. Opetusministeriön ja Opetushallituksen välinen tulossopimus vuosille [The development of language teaching. Performance agreement between the Ministry of Education and the Finnish National Board of Education] 2006-2008, 25.9.2006. Online: http://www.edu.fi/txtpage.asp?path=498,528,39390,40259,58828.

KIMMOKE: Kieltenopetuksen monipuolistamis- ja kehittämishanke 1996-2000. Loppuraportti [Project for the diversification and development of language teaching. Final Report] (2001) Helsinki: Opetushallitus. (Online http://www.edu.fi/julkaisut/kimmokeloppurap.pdf).

KIEPO – Kielikoulutuspoliittinen projekti [Project on Finnish Language Education Policies] (2007) www.jyu.fi/hum/laitokset/solki/tutkimus/projektit/kiepo/ (accessed 11.11.07).

Kumpulainen, Timo; Saari, Seija (eds.) (2006) Koulutuksen määrälliset indikaattorit, [Quantitative indicators in education]. Helsinki: Opetushallitus.

Latomaa, Sirkku; Nuolijärvi, Pirkko (2005) The language situation in Finland. In: Kaplan, Robert B.; Baldauf, Richard B. (eds.) Language Planning and Policy in Europe. Vol 1: Hungary, Finland and Sweden, 95-202. Online: http://www.multilingual-matters.net/cilp/003/0095/cilp0030095.pdf

Leijonborg, Lars (2007) Högre språk- och mattekrav ska ge gräddfil til högskolan. In: Dagens Nyheter 21.2.07. Online: www.dn.se/DNet/jsp/polopoly.jsp?d=572&a=620088 (accessed 5.11.07)

Luukka, Minna-Riitta/Pöyhönen, Sari (2007) Kohti tulevaisuuden kielikoulutusta. Kielikoulutuspoliittisen projektin keskeiset suositukset [Towards the language education of the future. The central recommendations of the project on language education policy]. Jyväskylä: Soveltavan kielentutkimuksen keskus. Online: www.jyu.fi/hum/laitokset/solki/tutkimus/projektit/kiepo/keskeisetsuositukset/suositukset (accessed 16.9.07).

Malmberg, Per (2000) De moderna språken i grundskolan och gynmasieskolan från 1960 och framåt [Modern languages in the comprehensive school and the upper secondary school from the 1960s]. Stockholm: Skolverket. Online: www.skolutveckling.se/digitalAssets/115632_historik.pdf (accessed 5.11.07).

McDonald, Trevor; Boyd, John (2000) Languages: the next generation. The final report and recommendations of the Nuffield Languages Enquiry. London: The Nuffield Foundation. Online: http://languages.nuffieldfoundation.org/filelibrary/pdf/languages_finalreport.pdf.

Nordic Council of Ministers (2006) Deklaration om nordisk språkpolitik, B 245/kultur [Declaration on Nordic Language Policy], passed by the Nordic Council on 2.11.2006 http://www.norden.org/sagsarkiv/sk/sag_vis.asp?vis=2&id=335.

Nyman, Tarja (1999) KIMMOKE. Seuranta- ja arviointitutkimuksen loppuraportti. Kieltenopetuksen monipuolistamis- ja kehittämishanke 1996-2000. Opetushallitus Moniste 28/1999, Helsinki. (Online http://www.edu.fi/julkaisut/kimmo3.pdf).

Piri, Riitta (2001) Suomen kieliohjelmapolitiikka. Kansallinen ja kansainvälinen toimintaympäristö, Jyväskylä: Soveltavan kielentutkimuksen keskus. Online: http://www.solki.jyu.fi/julkaisee/suomenkieliohjelmapolitiikka.pdf (accessed 2.10.07).

Saarinen, Sari (2007) Kieliä valitaan yhä vähemmän [Languages are being chosen less and less]. In: Tempus 3/07, 8-9.

Sajavaara, Kari (2006) Kielipolitiikka ja kielikoulutuspolitiikka [Language policy and language education policy]. Jyväskylä: Soveltavan kielentutkimuksen keskus. Online: www.jyu.fi/hum/laitokset/solki/tutkimus/projektit/kiepo/tavoitteet/Kielipolitiikka_FSFT.pdf (accessed 25.6.07).

Statistics Finland [Tilastokeskus] (2007) Population. Online: http://www.stat.fi/tup/suoluk/suoluk_vaesto_en.html (accessed 1.10.2007).

Takala, Sauli (1993) Language policy and language teaching policy in Finland. In: Sajavaara, Kari; Lambert, Richard D.; Takala, Sauli; Morfit, Christine A. (eds.) National foreign language planning: practices and prospects, Jyväskylä: Institute for Educational Research, 54-71.

Virtual Finland – Your window on Finland. Online: www.virtual.finland.fi (accessed 1.10.07).

Biodata

Chris Hall is professor of German at the