German dictionaries for the PC.

A survey from the perspective of the language learner[1]

Chris Hall

Twelve electronic German dictionaries (bilingual,

multilingual and monolingual) are tested and compared for their performance

under a number of headings: information content, on-screen presentation of

material, incorporation of hypertext and multimedia features, search facilities,

interactive features, use with other applications, use of dictionaries

together, and price. There are enormous differences in approach and quality

between the various dictionaries, but the best of them are extremely powerful

linguistic tools which can be utilised by language learners in a variety of

ways. Details of each dictionary's features and performance are included in an

appendix.

1. Introduction

Dictionaries have a long tradition. The

oldest surviving German book, Abrogans

(written in Freising in the second half of the 8th century), was a dictionary,

or more accurately a list of Latin words with their translations into Old High

German. The continuous dictionary tradition does not go back so far, but from

the late Middle Ages a large number of dictionaries have been produced,

including those by Dasypodius (1536), Adelung (1774-86), Jakob and Wilhelm

Grimm (1852-1960) and Konrad Duden (first published in 1880). Dictionaries

belong to the most heavily used and commonly purchased books, and nowadays most

households own one.

Dictionaries can be used for different

purposes. Bruton (1999:1) draws the principal distinction between “learning and

communicative use”, but within these categories we can further distinguish

between receptive and productive use, use for spoken or written language, and

use in various special fields. This has led to different types of dictionaries

for special purposes: learners’ dictionaries, pronouncing dictionaries, pocket

dictionaries, etc., as well as general dictionaries, which try to cover as wide

a set of circumstances as possible.

With paper dictionaries, the order of the

material clearly has to be fixed. Ever since the earliest dictionaries, the

entries have been placed in alphabetical order. There are exceptions to this,

such as thesauri and dictionaries of synonyms, in which material is organised

according to semantic criteria, but these have been a very small minority.

Alphabetical order has the advantages of simplicity and familiarity, but it

also has its disadvantages, as Rossner observes:

There is

no doubt that the time-honoured recourse of arranging entries alphabetically

has serious disadvantages for many users who are interested in the differences

in meaning between related words. At present such users have to buy a second

book and will presumably continue to be ill-served in this way until

micro-computers come with large enough memories (and small enough price tags)

to compete with multi-book (and costly-to-update) systems of reference.

(Rossner 1985:96)

Just a few years after this was written,

personal computers with the necessary power were widely available at affordable

prices, and in the 1990s a large number of electronic dictionaries came onto

the market. The flexibility of the computer has been used in different ways by

different dictionary manufacturers, leading to a variety of products which

offer far more than just freedom from a fixed alphabetical order. In the best

cases they are highly versatile linguistic tools.

The purpose of this study is to compare

the different solutions adopted in a number of existing products in order to

come to a judgement on the best practice currently available and to see where

improvements are still needed, paying particular attention to the needs of the

language learner.

Three general points should be made

before I proceed to the detailed analysis:

1) At present, electronic dictionaries are

used almost exclusively in conjunction with written language, which is the

classic domain of the computer. This situation is already changing, of course,

and with the rapid development of speech recognition technology the computer

is being used increasingly in conjunction with spoken language. This means

that in the future the needs of users in spoken language will have to be taken

more and more into account

[2]

.

2) Even within written language, different

user groups have different needs, and a dictionary which is adequate for some

purposes may not necessarily equally useful for others. One factor is the

native language of the users, as Neth and Müller (1997:117) observe:

Für jedes Spachenpaar sollte es genaugenommen zwei Sätze von Wörterbüchern

geben. Ein deutsch-englisch/englisch-deutsches Wörterbuch für deutsche

Muttersprachler soll helfen, bekannte deutsche Wörter in die Fremdsprache zu

übersetzen und zum Verständnis eines fremden Textes beitragen. Für

Englischsprechende müssen jedoch mehr Informationen über die Verwendung der

fremden deutschen Wörter enthalten sein: dafür müssen die englischen nicht so

ausführlich erläutert werden.

In fact, large scale dictionaries have

usually attempted to cater for speakers of both languages, e.g. by providing

information on grammar and usage of both languages and information on the

pronunciation of all, or all irregular, words. This is also encouraged by

commercial considerations, as it gives the publishers access to both markets.

Electronic dictionaries are potentially better suited to giving general

coverage than paper dictionaries because of their capacity for filtering out

unnecessary information (even though existing dictionaries do not make use of

this capacity, see point 3(e) ‘Interactive features’ below). None of the

bilingual dictionaries examined for this study was less adequate for the needs

of English-speaking learners of German than for German-speaking learners of

English.

3) I only looked at dictionaries on

CD-ROM which run on PCs. Some of these dictionaries also have Mac versions, but

others do not, and this seems to be one area in which developments for the Mac

have lagged behind the PC.

2. Advantages and

disadvantages of electronic dictionaries

Electronic

dictionaries have both advantages and disadvantages in comparison with paper

dictionaries:

a)

Advantages

·

Speed

and convenience when working on a computer;

·

Ease

of cross references, both within one dictionary, e.g. the two halves of a

bilingual dictionary, or between two dictionaries, e.g. a bilingual and a

monolingual one;

·

Different

types of searches are available, e.g. browsing, full text search, fuzzy search;

·

The

potential to use the data in the dictionary for other purposes, e.g. vocabulary

learning aids;

·

Results

of searches can be printed out or copied into a document on a word-processor;

·

Entries

can be modified (added to/corrected). A dictionary can thus be treated as a

project rather than a finished product, which is not really possible with

printed dictionaries.

·

Multimedia

features can be included, esp. sound, but also video for movement;

·

They

take up little space on bookshelves;

·

Price

(potential long-term price, with upgrades)[3].

b) Disadvantages

·

A

computer is needed to work with them (this rules out certain types of

dictionaries, e.g. pocket dictionaries and phrase books for tourists[4]);

·

Price

(current, initial price);

·

The

uncertainty of the medium (how long will CD-ROM be the standard?)[5];

·

It

is not possible to test them before purchase. This is a considerable

disadvantage for the more expensive dictionaries, but none at all for the free

products. It adds to the importance of reviews and comparative studies like the

present one.

It will be seen that the list of

advantages is considerably longer than the list of disadvantages. However, this

does not necessarily mean that electronic dictionaries are superior, as the

disadvantages, although small in number, may be serious for some users. Many of

the points mentioned above will feature in the detailed comparison below.

3. Features of

electronic dictionaries

In spite of the promise of the new

medium, a number of electronic dictionaries have had a remarkably short life,

including one of the early market leaders, Harrap’s

Multilingual Dictionary, which is no longer available. The Collins Series 100 Multilingual Dictionary

on CD-ROM is still available, but although it worked satisfactorily for me

in Windows 3.1, it did not run in Windows 95 or later versions. As these are

now the most common platforms and the publisher has no plans to update this

product or bring out a new one, I did not include the Collins Dictionary in the present study.

There is now a large number of technical

and specialist dictionaries on the market. For this study I have restricted

myself to general dictionaries, as these are the most useful to language

learners[6]:

1 Bilingual/multilingual

dictionaries

Langenscheidts

Handwörterbuch Englisch (PC-Bibliothek)

Oxford Duden German Dictionary

on CD-ROM

Bertelsmann’s

Euro-Wörterbuch

Euro Dictionary

Euroglot

WinDi

2 Monolingual

dictionaries

Duden Universalwörterbuch A-Z

(PC-Bibliothek)

Wahrig Deutsches

Wörterbuch

Duden

Rechtschreibung (PC-Bibliothek)

3 Pop-up

dictionaries

Babylon

QuickDic

Langenscheidts

Pop-up Wörterbuch XL

Some of these are computerised versions

of existing dictionaries from established publishers such as Langenscheidt,

Oxford University Press and the Bibliographisches Institut (Dudenverlag). In

these cases, an interesting question is to what extent they have simply fed

their printed texts into the computer (resulting in a paper dictionary on the

computer) or whether they have utilised the full potential of the computer in

their electronic products. In cases where there is no experienced dictionary

publisher behind a product, one important question concerns the quality of the

lexicographical material.

I have included two dictionaries which

are available free on the Internet in order to see how they compare with

commercial products and whether they are worth using. Of course, many users may

find a free dictionary useful even if it does not come up to the standards set

by commercial publishers.

In what follows, information on various

aspects of the dictionaries is presented under a number of headings. The

treatment of individual dictionaries is deliberately selective here. A

systematic description of the dictionaries examined is contained in summary

form in Appendix A.

a) Information

content

Size of

vocabulary:

Almost all the manufacturers give a figure for the number of entries or

headwords contained in their dictionary, but these are difficult to compare, as

they are expressed in rather vague terms, e.g. “rund 220 000 Stichwörter und

Wendungen” (Langenscheidts Handwörterbuch)

or “over 260,000 words and phrases” (Oxford-Duden).

Presumably this means approximately half this number for each language, but

exactly how words and phrases are counted is not made clear. E.g. is the word

‘term’ counted only once, even though the entry is divided into 14 sections in Langenscheidts Handwörterbuch and 11 in

the Oxford-Duden?[7]

The most reliable way to gauge both the

number and the quality of the entries is to subject each dictionary to a

detailed word test. For this purpose I have used the well-thought-out general

word test of 100 items in Neth/Swanson (1999:103), augmented by two tests of my

own (see Appendix B below). The results of these tests are included in Appendix

A. Neth and Swanson’s test was only suitable for bilingual dictionaries, as it

contained both German and English words. The best performers were Langenscheidts Handwörterbuch (91/100)

and the Oxford-Duden (81/100), and Langenscheidts Pop-up dictionary (which

is based on the Handwörterbuch) also

performed well with 75/84.

Detail of

entries: The

number of entries alone does not give

us a reliable indication of the coverage a dictionary provides. There is

enormous variation in the amount of information given in each entry, from a

single word to several pages of explanations including details of meaning,

pronunciation, grammar, usage and idioms (see figures 1-4 below).

Use of examples: In general, the larger

dictionaries of established dictionary publishers like Langenscheidt, OUP and

the Dudenverlag are the only ones able to provide a substantial number of

examples. The very brief dictionaries (e.g. Euro

Dictionary, QuickDic, WinDi) give no examples at all. There

has been some recent discussion of the role of examples in dictionaries, and it

may be that their usefulness varies with different linguistic tasks[8],

but I doubt that many language teachers or learners would like to do without

them. It is not only the number, but also the choice of examples which is

important. In her study of the Longman

Dictionary of Contemporary English, for instance, Nesi (1996) shows that

the dictionary does not always give sufficient or appropriate examples. I was

not able to test the appropriateness of the examples in the German dictionaries

under review, but clearly it is an aspect which all dictionary makers need to

look at carefully in further developing their products.

Current

vocabulary:

In order to establish whether the vocabulary in the dictionaries been adapted

and brought up to date for the new medium, or whether existing material from

paper dictionaries has been used, I used two tests on neologisms (20 items) and

computer terminology (20 items), both fields which are not usually covered well

in paper dictionaries and yet which will presumably be of special interest to

users of electronic dictionaries. They expect an up-to-date product for a

technologically advanced platform, and all users of these dictionaries are by

definition computer users.

The best of the bilingual dictionaries

was again Langenscheidts Handwörterbuch

with 9/20 and 12/20. Among the monolingual dictionaries the Duden Universalwörterbuch achieved

scores of 16/20 and 13/20, ahead of Wahrig

(10/20 and 11/20) and Duden

Rechtschreibung (13/20 and 10/20), although in the case of the latter it

must be remembered that it is a spelling dictionary and sometimes the entry

consists solely of the headword in question with no additional information at

all. Langenscheidts Pop-up dictionary

includes over 700 ‘Internet terms’, so its good score of 15/20 on computer

terminology was to be expected, but in fact it was outperformed in this respect

by the free Babylon pop-up dictionary

with 16/20.

Availability of

updates: It

is now common for multimedia encyclopaedias to offer not only Internet links

but also downloadable monthly updates (Encyclopaedia

Britannica, Encarta, etc., see

Schult 1999). Even some general (i.e. non-IT) publishers provide upgrades on

their websites, e.g. Lonely Planet

guidebooks[9].

It is therefore disappointing to see that only two of the dictionaries examined

(Babylon and WinDi) come with updates, which are an excellent way for them to

keep up with the rapid developments in vocabulary[10].

b) On-screen

presentation of material

Screen layout and

readability:

In printed dictionaries, space is at a premium and readability almost invariably

suffers. In electronic dictionaries there is no need for cramped presentation,

yet some of the traditional dictionary publishers seem to carry over the layout

of their printed dictionaries onto the screen. The screen layout of Langenscheidts

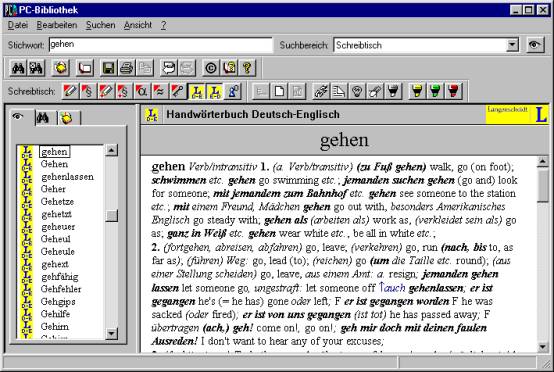

Handwörterbuch is packed full of information (see Fig. 1), and is only

saved by a good use of bold and italic fonts.

|

Fig

1: Langenscheidts Handwörterbuch

entry 'gehen' (part)

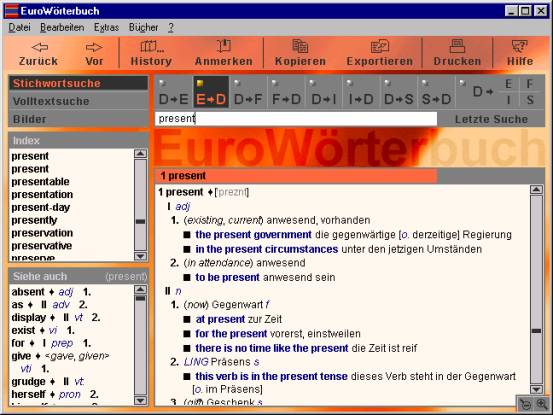

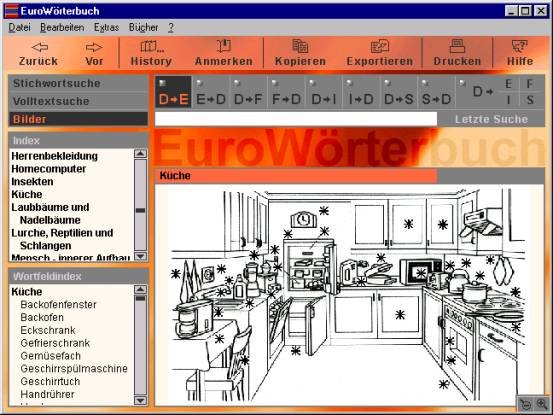

The Deutsches Universalwörterbuch has similarly packed screens, but with a less structured screen (e.g. less use of bold typeface). The entries in Bertelmanns Euro-Wörterbuch, which is a smaller dictionary and contains less information, are better spaced-out, see Fig. 2:

|

Fig

2: Bertelmanns Euro-Wörterbuch entry

‘present’

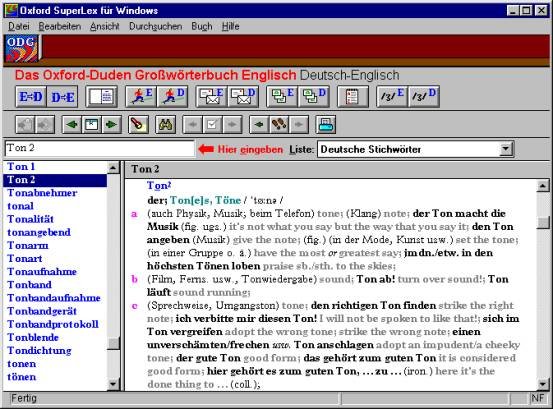

Fig 3:

Oxford-Duden entry ‘Ton’ (part)

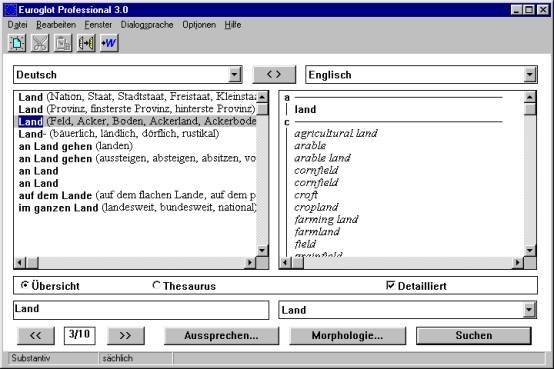

The most unusual of the dictionaries examined

here is Euroglot, which is not so

much a multilingual dictionary as a multilingual thesaurus, see Fig. 4.

|

Use of abbreviations:

An important space-saving device in printed dictionaries is the use of abbreviations.

With the enormous storage capacity of CD-ROMs, it is not necessary to use

abbreviations at all in electronic dictionaries, which is the approach taken

e.g. by the PC-Bibliothek. A different solution is adopted by Bertelsmann Euro-Wörterbuch, which does

use abbreviations e.g. for grammatical information, but provides a full version

and translation in a pop-up window at a click of the mouse. Abbreviations

not only affect the readability of the text, they also affect the way in which

searches can be done, see ‘full text search’ below.

c) Incorporation

of hypertext and multimedia (hypermedia) features

Hyperlinks: It is the concept of

hypertext which makes electronic dictionaries such powerful tools and gives

them their real advantage over printed dictionaries. Texts, e.g. dictionary

entries, are no longer restricted to a linear order, but can be connected via

hyperlinks which enable the user to jump from one text to a precisely determined

point in another. The best electronic dictionaries make superb use of this

facility, e.g. the dictionaries in the PC-Bibliothek,

in which a double click on any word in an entry will bring up the relevant

headword. For example, from the entry ‘Alter’ in Langenscheidts Handwörterbuch a double-click on ‘age’ or

‘seniority’ will take the user to the entries for these words in the English

section of the dictionary. Bertelsmanns

Euro-Wörterbuch has the same

facility, although in this case it tends to show just how many words are

missing in the other half of this much smaller dictionary. The Oxford-Duden has a less convenient way

of doing the same thing (highlighting the word and then clicking on a button).

These hyperlinks are particularly important in bilingual dictionaries, as they

enable users (a) to look up any unfamiliar words in the entry they have brought

up on screen, and (b) to bring together the information in both halves of

dictionary, thus enabling them to check which of a number of possible translations

is the most suitable. This is something which has always been regarded as

desirable, but which is very time-consuming with printed dictionaries.

Sound: Multimedia involves a combination

of text, sound, graphics or pictures and video. A combination of these elements

with hypertext is referred to as hypermedia. After hypertext, the most important

aspect of hypermedia for electronic dictionaries is sound, which is essential

for an adequate treatment of pronunciation. Printed dictionaries use various

transcription systems to indicate pronunciation, but these have always been

problematical, either because the systems themselves are not very satisfactory

(e.g. the ones used by many American dictionaries) or because many users were

not familiar with them, as is the case with the IPA transcription. It is somewhat

surprising that the electronic dictionaries do not show more enthusiasm for

this aspect of multimedia. Full sound for all headwords is offered only by

Bertelsmann Euro-Wörterbuch and

Euroglot (the latter on extra CDs).

Wahrig has sound for 8,000 “difficult

loan words”, the Euro Dictionary

has sound for all the phrases it contains, and there is a add-on sound component

for WinDi (which was not available

for testing). None of the other dictionaries, including the most comprehensive

bilingual dictionaries, have any sound component at all.

Video would be desirable for movement,

e.g. dance steps, gymnastic exercises, sign language (cf. Storrer 1999:110).

The Longman Interactive English Dictionary,

an electronic learner’s dictionary of English, contains eight short video

sequences depicting scenes from everyday life, but none of the German dictionaries

under scrutiny here include video.

d) Search

facilities

Various types of search are possible in

electronic dictionaries:

Browsing is the electronic equivalent

of looking up a word in a paper dictionary, searching through a list of entries

until the right one is located.

Headword search: The facility contained in

electronic dictionaries which really speeds up searches is the ability to type

in a headword and go straight to the entry. In fact, as the word is typed in,

the dictionary searches through the list of entries and usually locates the

right one before the word is complete, making the search even faster. All the

dictionaries (except two of the pop-up dictionaries, see below) offer these two

basic types of search. In the simpler ones these are the only two search types

available.

Full text

search: This

is a very useful facility, because it quite frequently happens that a word

which is not a headword in its own language is used in examples or in defining

a word of the other language. E.g. ‘gridlock’ does not form a headword in the

English section of Langenscheidts

Handwörterbuch, but it does occur as the English translation of the German

word ‘Verkehrsinfarkt’, and is successfully located in a full text search. A

full text search cannot work properly if there are abbreviations in the

entries, as is common practice in paper dictionaries. This is a further

important reason for avoiding abbreviations.

Fuzzy search: A fuzzy search finds not only

the exact word typed in, but also near misses. This is useful if the user is

not completely sure about the spelling of a word, e.g. ‘decipher’. The

spellings ‘desifer’ and ‘decypher’ produced 53 and 86 suggestions respectively

in Langenscheidts Handwörterbuch,

including the word I was looking for. The fuzzy search does not always work, of

course, and sometimes comes up with bizarre results, e.g. a search for

‘Schaltfläche’ resulted in ‘Kältewelle’. Of the dictionaries examined here,

fuzzy searches are only available in the PC-Bibliothek

and the Euro Dictionary, although

the Babylon pop-up dictionary has a

similar facility, making suggestions if a work is incomplete or incorrect.

Wildcards: The most common wildcards are

‘?’ for one character and ‘*’ for any number of characters (including zero).

This is useful if one is unsure about spelling, e.g. ‘dec?pher’, but also when

searching for a family of words. For instance, the search for ‘*ciph*’ in the Oxford-Duden came up with not only

‘cipher’ and ‘cypher’, but also ‘decipher’, ‘encipher’, ‘indecipherable’ and

‘undecipherable’, as well as some entries which contain the string ‘ciph’ such

as ‘distinguishable’ and ‘interpret’.

Inflected forms such as ‘nimmt’ from ‘nehmen’

and ‘geschwommen’ from ‘schwimmen’ are always a problem for dictionary makers.

The most common inflected forms have entries of their own in larger

dictionaries, usually simply referring the reader to the main entry. Not

surprisingly, the monolingual dictionaries are much more successful at locating

inflected forms than bilingual ones, but those dictionaries offering a full

text search clearly have a much better chance of finding inflected forms, as

they can search the complete text of the dictionary and are not limited to

headwords. A particular strength of Euroglot,

which was not among the top performers overall, is its impressive ‘morphology

recognition and generation facility’ covering all the inflected forms of every

single word in the dictionary.

Combined search:

Searches for multi-word units and idioms like ‘trip the light fantastic’ can be

time-consuming and frustrating in paper dictionaries. The more advanced

electronic dictionaries include combined searches with the Boolean operators

AND, OR and NOT. E.g. in Langenscheidts

Handwörterbuch, a full text search for ‘trip AND light’ or ‘trip AND

fantastic’ produces ‘ein Tänzchen aufs Parkett legen’ in the German entry

‘Parkett’, and ‘light AND fantastic’ leads to ‘das Tanzbein schwingen’ in the entry ‘Tanzbein’. In the PC-Bibliothek, a combined search can be

used in conjunction with a fuzzy search, so that ‘vorzügliche AND Hochachtung’

also finds the adjective with a different ending in ‘mit vorzüglicher

Hochachtung’.

Search within

entries: It

is often difficult to find information in long, complex entries in both paper

and electronic dictionaries, e.g. the entries for common words like ‘to make’

or ‘geben’. The dictionaries in the PC-Bibliothek,

the Oxford-Duden and Wahrig have good facilities for

searching within entries, which makes it much easier to locate information than

in their paper equivalents.

e)

Interactive features

Addition of

material: One

of the most fundamental differences between electronic and paper dictionaries

is the ability of the user to add material, either new entries or within

entries, or to make corrections to any errors that are discovered. This can

encourage users to adopt a new, more active way of working with dictionaries.

The most basic form is the facility to create new entries, which is contained

in the dictionaries in the PC-Bibliothek,

the Euro Dictionary and QuickDic. Users can either compose their

own entries, or enter material found elsewhere, e.g. on the WWW.

Annotation of

entries: Most

of the dictionaries examined here also allow the user to add material, e.g.

additional meanings or examples, or their own comments to existing entries.

Highlighting: The dictionaries in the PC-Bibliothek allow the highlighting of

material in entries in three colours. This is a very simple and effective way

of individualising the dictionaries and marking material which is of particular

relevance to users.

Facility for

filtering out information: In

the larger dictionaries, the sheer mass of information is sometimes a problem. As Sussex et

al. (1994:142)

observe, “excessive information can be a learning barrier”, especially for

non-advanced students. Ideally, the user would be able to filter out

unnecessary detail when searching through long and complex entries. Black

(1991:164) suggests a modular dictionary in which definitions and examples are

addressable independently of one another, and which could even include further

options such as ‘brief definitions’ or ‘extended definitions’. None of the

dictionaries examined here contain a facility for filtering out information, but it is technically feasible and

would be desirable for longer entries. In fact, electronic dictionaries have

less of a problem in this regard than paper dictionaries because space is not

at a premium, which means that they should be able to structure their entries

in a more user-friendly fashion, and also because searches within entries make

information easier to locate. But the larger dictionaries could still be

improved by allowing the user to decide how much information is presented on

screen.

f) Use with other applications (word-processing/Internet)

Hot

keys/Buttons:

All of the dictionaries examined allow access from within other applications,

e.g. word-processors, via a hot key or a button. This works particularly well

in the PC-Bibliothek: pressing a

user-defined hot key in the word-processor causes the word under the cursor to

be highlighted, after which the computer switches to the PC-Bibliothek and looks up the word automatically. In this way it

takes only about 1 second to look up a word. Other dictionaries have similar,

if slightly less convenient look-up procedures.

Pop-up dictionaries:

This is the latest form of electronic dictionary, designed solely for use

within other applications, especially for internet users. The dictionary runs

in the background while an internet page or word-processor is on the screen.

A mouse click on a word on the screen opens up a small coloured window with

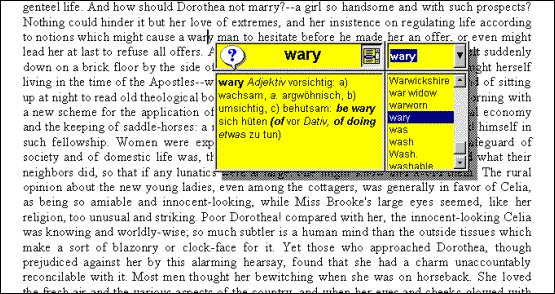

the translation of the word under the cursor (see fig. 6).

|

Fig. 6: Langenscheidts Pop-up Wörterbuch XL entry ‘wary’ (list window)

Two of the pop-up dictionaries tested, Babylon and QuickDic, are shareware products which can be downloaded free from

the internet. The licence is valid for 100 days, but can be renewed for further

100 day periods without restriction. Babylon

is an impressive product, both in the size of its vocabulary and its

user-friendliness[11].

Langenscheidt’s commercial pop-up is also very easy to use, and unsurprisingly

in view of its provenance, performed well in the vocabulary tests.

Transfer of material between applications: All of the dictionaries, with the exception of Babylon, allow material to be copied to the clipboard and pasted into other applications, e.g. word-processors. This can be a very useful facility for language learning activities, especially vocabulary learning.

g) Use of dictionaries together

Bilingual and

monolingual dictionaries: It

has always been regarded as desirable practice for learners to check the

information they find in a bilingual dictionary against the more detailed

information contained in a good monolingual dictionary. With paper dictionaries

this was extremely time-consuming and therefore rarely done. Electronic

dictionaries have changed this situation completely: it is now a very simple

matter to switch between bilingual and monolingual electronic dictionaries,

especially if they are on a joint platform, as is the case with the

dictionaries in the PC-Bibliothek.

Bertelsmann’s Euro-Wörterbuch and Wahrig are also on a joint platform, BEEBOOK, but it is not as quick and

convenient to operate as the PC-Bibliothek.

Multilingual

dictionaries:

Bundles of dictionaries in several languages may be useful for less advanced

learners, e.g. schoolchildren, many of whom will be learning more than one

foreign language. At an advanced stage this advantage becomes less important in

comparison with a comprehensive coverage of a single language or language pair.

Several comprehensive dictionaries in different languages on a single CD-ROM

would also push the price up, so the larger dictionaries are usually sold

separately.

h) Price

Current prices: The variation in price

between electronic dictionaries is as great as the variation in quality, and

unfortunately there is no direct link between the two. The electronic

dictionaries produced by the major dictionary publishers are generally more

expensive than their paper equivalents. The most extreme example of this is Langenscheidts Handwörterbuch, the

electronic version of which is over

two and a half times the price of the printed work. On the basis of their

performance, the higher prices of the electronic versions are justified, but on

the basis of the relative production costs of CDs and books they are not. On

the other hand, some of the shorter electronic dictionaries, which are clearly

aimed at a wider market, are already very competitively priced, e.g. Bertelsmanns Euro-Wörterbuch.

Outlook on

prices:

Langenscheidt’s pricing policy is exceptional, and there are indications that

prices are starting to come down, as it the case with encyclopaedias (cf.

footnote 3 above).

Shareware and Internet

dictionaries:

two of the pop-up dictionaries examined here are completely free of charge.

There are also many other electronic dictionaries which can be accessed free of

charge via the internet. These have not been included in this survey, but see Storrer/Freese

(1997) and Breindl (1998).

4. Electronic

dictionaries as language learning tools

From the point of view of language

learners electronic dictionaries are superior to paper dictionaries in a number

of ways:

Improved

searches make

it easier to find information in the dictionary, especially for learners, whose

lack of knowledge and intuition about the language often make paper

dictionaries difficult to use. Of particular importance are: the full text

search, fuzzy search, search for inflected forms, search for multi-word units,

and the search within longer entries.

Vocabulary

learning device:

Is it possible to bring together vocabulary from a certain field (e.g.

computing terms) and transfer it to a word-processor or print it out for use in

language learning. A full text search for ‘computer’ in the English-German half

of Langenscheidts Handwörterbuch resulted

in a list of 168 items, 308 in the German-English half. These searches can be

used to compile vocabulary lists of word families (e.g. names of trees), but

their success depends on how well the entries are labelled in the dictionary.

All of the dictionaries could be improved in this respect. In the Oxford-Duden, for example, a full text

search for ‘tree’ in the English-German half resulted in a list of 105 items,

whereas a search for ‘Baum’ in the German-English half uncovered only 31 items,

indicating an unevenness in the way the concepts are labelled in the different

halves of the dictionary. However, even though they are yet far from perfect,

electronic dictionaries are clearly far superior to paper dictionaries as

vocabulary learning devices.

Reading: Perhaps the most exciting

development recently has been the arrival of pop-up dictionaries, which offer

an even more convenient format for learners reading foreign language texts than

the conventional electronic dictionaries, providing them with glosses to

unfamiliar words at a click of the mouse[12].

Writing: More and more writing is

being done on word-processors, and this applies to writing as part of the

language learning process, certainly for advanced learners. All of the

dictionaries are very easy to use from within word-processors and provide help

with writing in the foreign language. Even the Babylon and Langenscheidt

Pop-up dictionaries, which are

designed to help native speakers of German read English texts, can be utilised

for writing by learners of German: if they type an English word and click on

it, the pop-up dictionary will show the German equivalent. In addition to

search facilities for words in the foreign language, most learners will find

help with grammar useful when writing.

Grammar: Many printed dictionaries

offer a brief grammatical outline of the language(s) in question as well as

grammatical information in the individual entries. Most of the electronic

dictionaries tested here provide little or no specific information on grammar,

although some of them do provide information indirectly through examples. The

best grammar sections are in Wahrig,

which shows grammatical information in a small yellow window at a double-click

on a grammatical code in an entry, and the Oxford-Duden,

which has separate short grammar sections on English and German, but does not

provide any links from the dictionary. Euroglot

contains an impressive ‘morphology recognition and generation facility’ which

gives the full list of inflected forms of nouns, verbs and adjectives, and WinDi contains a conjugation module,

which gives all the inflected forms of verbs. Overall, however, this is an area

in which there is room for improvement.

Translating: Translating is first and

foremost a professional activity, of course, but it is usually seen as relevant

in language learning, too, especially at an advanced level. This view is

justified by the fact that translating and interpreting are activities which

people with a command of a second language are frequently required to do, and

it therefore makes sense to practise

them in language learning. The help that electronic dictionaries can offer when

translations are done on a word-processor is quite obvious, in my experience

they have an enormous impact on both the speed and the ease with which

translations can be done.

Pronunciation: Most of the dictionaries

examined in this study do not include sound, which is regrettable, as the

ability to give examples of pronunciation in its original medium is potentially

one of the greatest advantages electronic dictionaries have over paper

dictionaries. Some of the dictionaries include details of pronunciation in

phonetic transcription, but although this was the best books could do, it is

unnecessary on CD-ROMs and is less than satisfactory, not least because many

English-speaking learners of German are not familiar with IPA[13].

Use of

dictionaries together:

Advanced learners have always been encouraged to use bilingual and monolingual

dictionaries together, as bilingual dictionaries do not usually contain as much

detail or as many examples of use as monolingual dictionaries. Now this is easy

to do, especially with Langenscheidts

Handwörterbuch and the Duden

Universalwörterbuch in the PC-Bibliothek.

Some of the dictionaries include more than just one pair of languages, but from

a language learning point of view it is far more important to be able to use a

bilingual dictionary and a monolingual dictionary together than to be able to

use several different languages at the same time.

5. Conclusion

The perfect electronic dictionary does

not exist yet, and presumably never will. As with printed dictionaries, there

will continue to be different electronic dictionaries for different user groups

and different purposes. However, the detailed study undertaken here shows that

the best of the current electronic dictionaries are already very good indeed,

and as with other aspects of the computer, the development is continuing at a

very fast pace.

On the whole the best products come from established dictionary makers, who have not simply relied on their top class lexicographical material, but have also invested in the development of efficient and user-friendly software to make the material accessible on the computer. Among the bilingual dictionaries, Langenscheidts Handwörterbuch not only came out top in the word tests, but is also a user-friendly product with excellent search facilities and interactive features. Its main drawback is its high price. The Oxford-Duden not far behind the Handwörterbuch in its lexicographical material, but it is not quite so convenient to use. Bertelsmanns Euro-Wörterbuch has a much smaller vocabulary, but the on screen presentation is excellent and it scores well in its use of multimedia features, with sound for all headwords and some illustrations. It is excellent value for money and is suitable for beginners and intermediate learners, whereas advanced learners need the broader vocabulary and greater detail which the larger dictionaries provide.

Among the monolingual dictionaries, the Duden Universalwörterbuch A-Z performed well and is very easy to use together with Langenscheidts Handwörterbuch in the PC-Bibliothek.

Of the dictionaries from non-established dictionary makers, Euroglot is an imaginative product with some impressive features (sound for all headwords, morphology recognition and generation facility), but I suspect that most language learners will find a multilingual thesaurus less useful than a traditional dictionary, which is bound to affect its sales potential. It also has quite a limited vocabulary.

The most recent development are pop-up dictionaries, which make superb use of the technology and represent a real leap forward in the reading of foreign language texts on-line. Langenscheidts Pop-up Wörterbuch XL performed extremely well, but the free Babylon dictionary was not far behind, and is one of only two dictionaries so far to offer updates via the Internet. As yet, both these dictionaries are still only available in one direction (English into German), but Langenscheidt is preparing a German-English pop-up which should be available in the near future.

A few years ago, Willem Meijs spoke of “the imminent demise of the dictionary as a book” and predicted: “In a decade or so, on-line dictionaries on disk or CD-ROM will no doubt be the norm rather than the exception” (1992:152). There is no indication yet that this prediction is about to come true, but for those learners who have access to a computer, electronic dictionaries undoubtedly have many advantages over paper dictionaries for language learning purposes.