Foreign language learning with the new media:

between the sanctuary of the classroom and the open terrain of

natural language acquisition

Dietmar Rösler

In this article I will discuss the

importance of the new media for foreign language learning in four steps.

·

Step

one will look at changes in foreign language learning brought about by the

advent of the new media.

The

second and third steps belong, today at least, to two different realms of

science fiction:

·

Step

two briefly addresses how the internet could be used in co-operative

development of teaching material - there are no technical elements of science

fiction here, the futuristic element lies in the organisation of the production

and distribution of teaching material.

·

Step

three, on the other hand, is proper science fiction: I will ask whether natural

language acquisition could be imitated in an artificial virtual world of the

target language and culture and whether this would actually be a desirable

development.

·

Step

four, finally, returns to the real world to take a look at a successful

internet reading course provided by the Goethe-Institut.

This

article will neither cover the development of CALL software

[1]

nor address the question as to whether

a new paradigm of foreign language learning has evolved as a result of the

new media and of constructivist thinking. The former won't be covered due

to lack of space – even a publication in the WWW has to set its limits not

because of lack of volume but out of consideration for the reader. The latter

simply doesn't interest me: whether a new paradigm evolves or not is something

which the history of the subject has to determine in fifty years time or more,

discussions about it now can only be regarded as another example of the growing

trend of research being replaced by academic marketing.

1. How CD-ROM, email and the WWW can compensate for

some of the shortcomings of classroom based foreign language learning

The key question for me in the debate

about the role of the new media in foreign language learning is: (How) Do

the new media contribute towards enhancing successful natural learning within

what, for want of a better alternative, I will continue to call foreign language

learning in the classroom

[2]

? Sweeping statements about how textbooks are being replaced

by 'authentic' telecommunication, assumptions about autonomous learners which

haven't taken into account the constraints of learning in educational institutions,

and declarations about the the role of the teacher being solely that of a

facilitator, all these undermine

[3]

a differentiated discussion about what the new media can

contribute to the individualization of learning processes within the classroom

and about how a productive balance can be created between the function of

the classroom as a didactic sanctuary and the exciting challenges of autonomous

and discovery learning

[4]

.

Different media play a different

role in integrating aspects of natural learning into the classroom. CD-ROM

teaching material is as producer oriented as the current printed textbooks. The

fact that a CD-ROM offers multimedia presentations of its contents and

hypertextual access makes it a good medium for conveying information on clearly

defined subjects, for example on certain Landeskunde

topics which do not require up-to-the-minute information. In these cases a

CD-ROM may be of greater value than the WWW with its inherently chaotic

searches and representations. Teaching material on CD-ROM does, however, share

the main weakness of current printed and cassette based teaching material: its

contents and - despite the seemingly interactive interface - ultimately the

study path of the learner too is predetermined by the producers of the CD-ROM.

The content is hardly ever

predetermined where electronic mail is utilized for foreign language purposes.

Emails are texts on the border between verbal and written language. Written and

read, they nonetheless display many of the characteristics of spoken language

in terms of choice of register and the high tolerance of mistakes.

The 1:1 relationship in language learning,

traditionally in the form of individual tuition in the interaction between

a teacher and a learner, calling to mind the language masters of former centuries

and which today is usually only to be found in private schools is, with the

advent of email, once again gaining ground. It has re-established itself at

the end of the twentieth century, beyond the affluent private pupil scenario,

in the form of alternative co-operative concepts, learning partnerships such

as the Tandem set-up, in which two individuals with different mother tongues

alternate the role of teacher – or to be more precise, that of the language

and culture expert – and learner

[5]

. Tandem learning has now, per email

[6]

, become a place of learning which transcends the necessarily

shared location in the original Tandem concept. In contrast to the classical

Tandem, using email Tandem means that the communication is written and asynchronic,

a bonus in a learning and teaching situation, in which the enthusiasm for

communicative language teaching often permits the pendulum to swing too far

to the side of spoken language; the functional communicative writing in emails

can enable it to be swung some way back towards the other side.

Giving a learner the possibility to

interact directly with a native speaker from the target culture is one common

use of email in foreign language learning, but it is certainly not the only

one. Email can also be used as a speedy variation of the old idea of class

correspondence and even for rather complex co-operations between groups of

learners in different cultural environments

[7]

. It can also play a part in teacher training: Tamme &

Rösler (1999) describe how a 1:1 email tuition for Chinese students of German

as a foreign language was introduced into the training of future teachers

of German at Gießen university.

Email can overcome some of the

constraints of classroom-based learning by providing a channel for real and

speedy interaction between learners and native speakers in the target language.

But, as always, the medium is not the message

because if people have nothing to say to each other then it doesn't really make

any difference in which medium they don't say it.

This difficulty persists for all

teachers and all learners, it won't go away by simply replacing conversation

classes by chat rooms and letters by emails.

While CD-ROMs are probably best

used for information retrieval of Landeskunde

activities and are less suited as material for a complete ab initio language course, and while the advantage of email and

chat rooms lies clearly in their providing swift contact between learners or

between learners and tutors, the use of the internet is more varied. It offers

different possibilities for those involved in foreign language learning:

-

up-to-the-minute

[8]

information on the target language and culture which hasn't

been produced specifically for language students and which is just there to

be listened to, read or looked at,

-

aids needed for language learning

such as grammars or dictionaries,

-

attempts to compile and adapt for

language learning purposes the data available in the internet,

-

so-called

chat rooms in which people can communicate directly with one another,

-

foreign language learning material

which has been produced specifically for the internet and

-

forums in which teachers and

learners can communicate with one another about teaching and learning.

The use of teaching material in the

internet or of sites relevant for teachers is becoming a commonplace activity.

The Goethe-Institut server for instance, which currently consists of around

23,000 WWW pages

[9]

, registered about 32,500 visits per day in January 2000,

which is slightly more than a million visits that month. Assuming that each

user calls up five pages on average, then

the Goethe-Institut site is currently being visited by about 6,500

people every day

[10]

.

2. Could the internet provide the framework for

co-operative production of learning and teaching material?

The internet supports both centralizing and

decentralizing activities at the same time and thus could facilitate the

collection and provision of good teaching and learning ideas which, taken from

the world-wide diversity of classroom experiences, could be used in adapted

form for concrete situations in specific places without a limiting, centralized

teaching model being imposed. One could even imagine the entire future

production of teaching material being altered thoroughly by this possibility of

simultaneous centralizing and decentralizing.

It would be possible, with the help of databases of

existing teaching material cut up into small units and interlinked, to exploit

all the current material on offer and, at the same time, be able to establish

exactly where the genuine deficits are, where writing new material and feeding

it into the database would be really worthwhile and not simply a case of reinventing

the wheel. This could stimulate the development of a multitude of teaching and

learning material of various national, regional and other specific adaptations

and variations, of different approaches to topics at varying stages of

progression and with references to different social, geographical and cultural

backgrounds, all linked with a variety of classroom activities. Texts which

weren't originally written for language learning could also be integrated,

together with suggestions of how to deal with them and linked with teachers'

forums supporting classroom activities.

This vision of a pool of teaching material contrasts

sharply with the real virtual world in which many search but few find what they

are looking for, in which aborted attempts and material of doubtful didactic

value can be found side by side with good ideas, and in which the question of

assessment and quality control is still in its infancy, despite hopeful

indications such as certain hompages developing a trustworthy reputation for the

links they provide to quality sites.

Despite this reality it is an open question whether

teacher training seminars will be able to pool their resources in order to

prevent the huge waste of parallel production and adaptation of material,

and whether publishers and authors of teaching material will be able to anticipate

this development and will create appropriately empty spaces which can then

be developed in a decentralized fashion

[11]

.

3. Science fiction:

natural learning in an artificial environment

Will learners who are physically outside the target

language area nonetheless one day, thanks to virtual reality, be able to learn

the language in a quasi-natural, rich linguistic environment, structured in

such a way that they experience few of the disadvantages which can be associated

with natural second language learning? Can natural foreign language learning

outside the target language area be boosted by a progression from tele-vision

and tele-hearing to tele-experience? Two different versions of tele-experience

in foreign language learning

[12]

present themselves. On the one side is a combination of chat

rooms and current virtual worlds, on the other is a purely artificial version,

the realisation of which is, from today's perspective, pure science fiction

and whose desirability might even be questionable.

The first version is a tele-experience from real

person to real person mediated by avatars who represent them. In this model,

learners as avatars in a virtual learning world can adopt any role they want,

they can change their regional origin, their social class or their gender just

as they can alter the outer appearance of 'their' artificial figure. All the

questions which make this form of communication in chat rooms or virtual worlds

so interesting for its non-language learner users apply here too: What is my

self, who is my opposite number in cyberspace? How can I communicate with

partners whose identities are constantly changing? These questions about

identity, which are as difficult to answer as they are exciting for those who

playfully enter a virtual world, become a problem when this form of

communication is functionalized for the purposes of institutionalized foreign

language learning. Will there be any elements of cultural context or

intercultural understanding left in this type of interaction or will the

arbitrariness of identities lead to the exclusion of anything which is

'difficult' and could disturb or even interrupt the flow of communication; will

anything which gets in the way of smooth communiation be eliminated? Will the

result be a kind of lowest common denominator, a McTalk?

The second version is pure science-fiction and plays

with the paradox of completely artificial natural communication. It is the most

exciting and most problematic model of foreign language learning per virtual

reality, one which won't hit the market within the near future - if indeed it

ever does – and one which avoids all the problems which can arise when native

speakers of the target language and learners of that language communicate in an

institutionalized context by providing a complete and complex cyberscript which

constantly gives the learners the feeling that they are participating in a

natural tele-experience, although they are, in fact, in the middle of a

classroom setting, the like and the scope of which has never been seen or

imagined before. In this model, all the participants communicating in the

virtual world, apart from the learners themselves, all the cultural

information, every form of behaviour, each moment of intercultural

misunderstanding, of joy etc. is completely scripted. The world that the

learners 'enter' is either populated by artificial figures in artificial spaces

or else by live actors and authentic original sounds recorded in scenes which

were shot like those in a foreign language learning film. The learners move

seemingly freely in a target language environment, which reacts appropriately

to their linguistic and non-linguistic behaviour; in it people are amused by

their lack of background knowledge or help them out with information, are

either friendly or not, and so on. The complex script reacts in a quasi natural

way to what the learners say and do, it isn't a film which is being shown, the

learners themselves are part of it.

I don't, at this juncture, wish to address the

ethical and moral questions which are automatically raised by the idea of such

total manipulation, instead I would like to position this model in the didactic

discussion. In the context of institutionalized foreign language learning

outside the target language area – and it is only this situation I am talking

about, as the target language area itself offers different possibilities for

linguistic interaction – two basic problems dominate: How can learners be

involved in meaningful interaction in the target language? And how can the

target language and culture be represented in a comprehensive and

differentiated manner? As far as involving learners in interaction in the

target language is concerned, foreign language teaching has frequently both

prematurely and inaccurately announced that a solution has been found – one

only has to remember how complex simulations or even simple role-playing in the

classroom were proclaimed to be natural communication.

As far as its material base is concerned, foreign

language learning has moved from textbooks to storing material on tapes,

cassettes and videos and linking these with the textbooks, it has moved on to

CDs and is now using material from the internet. A multitude of forms of

material has emerged which depart ever further from the notion that a textbook

could or should determine the entire learning process. Instead, the idea of the

textbook as a quarry has gained ground and, with it, the textbook itself has

retreated in the face of the movement towards learning in partnership in

situations of genuine communication. From this vantage point, the notion of

artificially creating natural communication in cyberspace would seem to be a

step backwards, didactically speaking, because it would be creating nothing

less than a giant textbook, based on the principle of simulation. But this

assessment doesn't take into account that such a cyberspace endeavour no longer

suffers, as traditional textbooks did, from the (unavoidable) reduction of

having to select elements of the target culture according to a

linguistic-communicative progression, which, due to their linear nature, books

and cassettes had and still have to do. Wouldn't the interaction between a

learner and an almost unlimited number of native speakers which, in the real

world, can only happen in the target language area, introduce a whole new

opportunity for natural learning into a classroom based learning environment?

Answers have not yet been found to these questions

but cyberspace, as a theoretical model, offers an interesting solution to the

problem of how to harness the power of natural language acquisition without

losing the positive aspects of structured classroom learning. This being pure

science fiction, I'll conclude with a look at a programme in the real virtual

world which tries to allow learners to make use of the internet while retaining

the advantages of guided learning.

4. Guided reading

on the internet: the case of jetzt-online

If the receptive skills of the learners

are built up as part of a language course from the very beginning

[13]

, it will be possible to partially release them at a fairly

early stage from the prescribed world of the textbook with its rigid progression

into the world of 'real' contact through media. The further away the place

of learning is from German-speaking areas or from centres with German tourists

and business connections, the more important the role the new media have to

play. The internet, particularly, is capable of providing up-to-the-minute

current affairs and other aspects of Landeskunde; however, coupled with this source is the problem of becoming

„lost in hyperspace“. A language learning internet version

[14]

of jetzt, the Süddeutsche Zeitung's supplement for young

readers, was developed at the Justus-Liebig-Universtität Gießen in co-operation

with the Goethe-Institut München; it attempts to combine the open world of

the internet with didactic sanctuaries of different degrees, selected according

to the needs of the users.

Reading is the main focus of this programme, even though,

as the homepage in Fig. 1 reveals, viewing comprehension (with the current

edition of the Tagesschau) is also

part of the package, and a chat-room is on offer

[15]

.

Fig. 1: Homepage of jetzt-online

The programme addresses individual learners and teachers

separately, in this article I will only give examples of its use for the individual

learner

[16]

.

The programme offers texts which are presented simply

as reading matter and are accessed via thematic selection, and texts which

are furnished with different tasks and exercises and which introduce different

reading strategies. The tasks differ in their degree of openness. At one end

of the spectrum are those which remain totally within the realm of traditional

language learning activities and which could also be found in a traditional,

'paper' textbook; at the other end are those which are specific to the internet

and introduce navigation skills while at the same time protecting the learners

from getting lost in hyperspace. Fig. 2 shows a reading text from the programme

which contains links of different degrees of openness.

www.goethe.de/z/jetzt/dejart65.htm

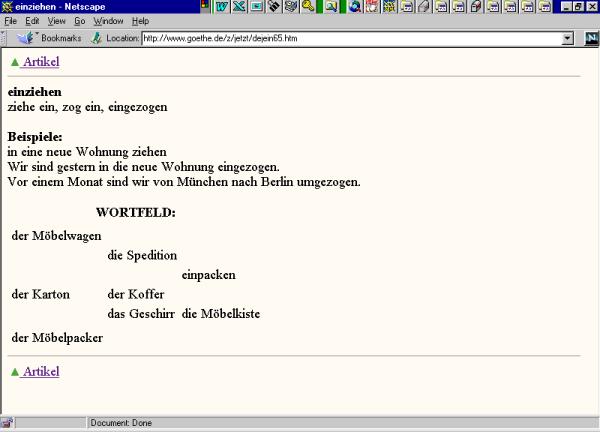

Blue links provide assistance in the form of brief

information on grammar, on idiomatic expressions, on the context of lexical

elements etc., an example – zog sie bei

einer neuen Freundin ein - can be seen in Fig. 3. This type of information

is always to be found in textbooks, work sheets etc. How helpful it is in any

individual case depends on the linguistic proficiency of the learner in

question. It is important for learners to know that, when calling up blue

links, they remain in a shielded area in which they aren't overtaxed. The lack

of contrastive components indicates that it is, as most commercially produced

printed teaching material, a 'germanocentric' work, produced in the German

language area. The nature of the internet does however allow (as indicated in

chapter 3) for decentralized alternatives, produced by teachers or learners in

different parts of the world, to be integrated into this central programme.

Fig. 3: Basic linguistic support as part of the

reading programme

www.goethe.de/z/jetzt/dejein65.htm

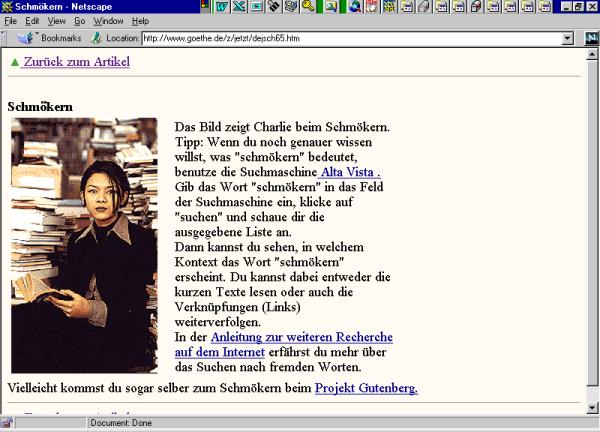

Beyond these blue ones, there are two further types

of links. The red ones lead, without any didactic preparation, straight to

internet pages – for instance to homepages of organisations – and hence

straight to up-to-the-minute information on a particular topic or institution.

The green links lead learners to tasks which couldn't be solved without the

internet. Fig. 4 illustrates this with an example of a task involving the word schmökern. Using Alta Vista, the learners

have to find, compile and discuss contexts for this verb.

Fig. 4: Making didactic use of a specific feature of

the internet: searching for contexts of a given word

www.goethe.de/z/jetzt/dejsch65.htm

These links are not limited to providing textual

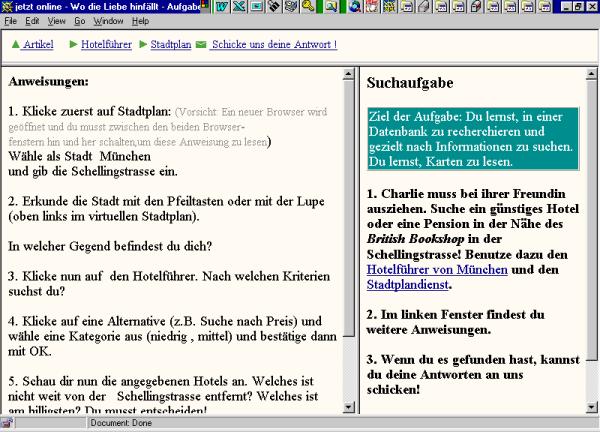

assistance for comprehension. Figures 5 and 6 show examples of a more complex

task which can only be addressed by exploring the net. Picking up the story in

the text in Fig. 2 – Charlie has to leave home – the task in Fig. 5 is to help

her find a suitable hotel in Munich close to her favourite bookshop.

Fig. 5: An internet based Landeskunde task

www.goethe.de/z/jetzt/dejfra65.htm

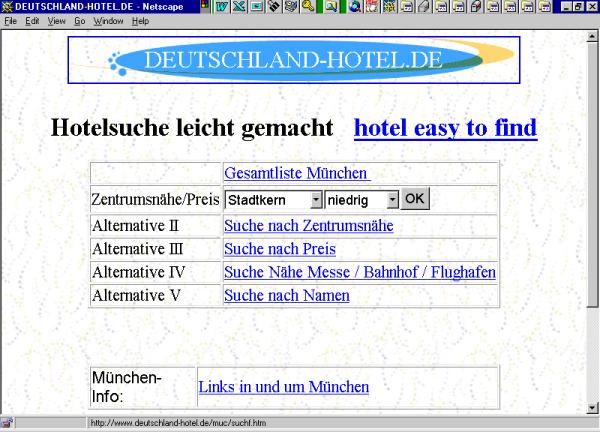

With the help of an excerpt from a map and using the

hotel guide for Munich in the internet (cf. Fig. 6), the learners have to

develop an optimizing strategy: which hotel is reasonably priced and nonetheless

located centrally enough for Charlie's needs?

Fig. 6: Making use of a non-didactic internet page

within an internet-based Landeskunde task

http://www.deutschland-hotel.de/muc/muenchen.htm

Incorporating the internet into teaching German as a

foreign language, especially in countries which are far away from

German-speaking areas, will become increasingly important. Students will want

to work with texts which are didactically prepared on different levels as

described here, search completely independently for information or simply

establish contacts via email or chat rooms. The new media will not solve the

basic problems of learning a foreign language outside the target language area

but they do enable teachers to react to the existing limitations in an

innovative and imaginative way and permit the boundaries of classroom learning

to be pushed back further by integrating elements of natural language

acquisition.

References

Estevez, M.; Lovet, B;

Wolff, J. (1989) Das Modell TANDEM und die interkulturelle Kommunikation in

multinationalen Sprachschulen, in: B-D. Müller (Ed.): Anders lernen im Fremdsprachenunterricht. Berlin etc., 143-162 .

Hess, H-W. (1998)

DaF-Software in der Anwendung – 'Alter Quark noch breiter'? In: Informationen Deutsch als Fremdsprache,

25, 1, 54-71.

Legutke, M. (1997) Redesigning the foreign language classroom. In: Perspectives (TESOL Italy), 23, 1,

27-43.

Little, D. (1994) Learner autonomy: A theoretical construct and its

practical application. In: Die Neueren Sprachen, 93, 5, 430-442.

Little, D.; Brammerts, H. (Eds.) (1996) A guide to language learning in tandem via the Internet. CLCS

Occasional Paper No. 46, Summer, Dublin, Trinity College.

Müller-Hartmann, A.

(1999) Auf der Suche nach dem 'dritten Ort': Das Eigene und das Fremde im

virtuellen Austausch über literarische Texte. In: Bredella, L.;

Delanoy, W. (Eds.) Interkultureller Fremdsprachenunterricht. Tübingen 1999, 160-182.

Rösler, D. (1998) Autonomes Lernen? Neue Medien

und ‘altes’ Fremdsprachenlernen. In: Informationen

Deutsch als Fremdsprache 25,1, 3-20.

Rösler, D. (1998a) Deutsch als Fremdsprache außerhalb des deutschsprachigen Raums. Ein

(überwiegend praktischer) Beitrag zur Lehrerfortbildung. Tübingen: Narr.

Rösler, D. (1999) 21 Anmerkungen zur Entwicklung

von Lehrmaterialien im Kontext der Neuen Medien. In: Bausch, K-R. et al. (Ed.) Die Erforschung von Lehr- und

Lernmaterialien im Kontext des Lehrens und Lernens fremder Sprachen.

Tübingen: Narr, 189-196.

Rösler, D. (at press)

Fremdsprachenlernen außerhalb des zielsprachigen Raums per virtueller Realität.

In: Fritz, G.; Jucker, A. (Eds.) Kommunikationsformen

im Wandel der Zeit. Tübingen: Niemeyer.

Tamme, C.; Rösler, D.

(1999) Heranführung an den autonomen Umgang mit Neuen Medien im

Fremdsprachenunterricht und in der Lehrerausbildung am Beispiel von

E-Mail-Tutorien. In: Fremdsprachen lehren

und lernen, 28, 80-98.

Ulrich, S.; Legutke, M.

(1999) Neue Medien in der Lehrerfortbildung. In: Fremdsprache Deutsch, 21, 39-44.

Biodata

Nach dem Studium der Publizistik und Germanistik an der FU Berlin arbeitete Dietmar Rösler in den Germanistikabteilungen des University College Dublin, der FU Berlin und des King's

College der University of London. Seit 1996 ist er Professor für Deutsch als Zweit- und Fremdsprache an der Justus-Liebig-Universität Gießen. Zu seinen Forschungsschwerpunkten

gehören: das Verhältnis von gesteuertem und natürlichem Zweit- und Fremdsprachenlernen, Lehrmaterialanalyse, Interkulturelle Kommunikation, Grammatikvermittlung, Technologie und Fremdsprachenlernen. Ausführliche Informationen finden sich unter: http://www.uni-giessen.de/~g91010/roesler.htm